The things we talked about

Moyra Davey, Dorine van Meel, Ruth Buchanan, Marie Shannon, Alicia Frankovich, lightreading, Hue & Cry

Curated by Abby Cunnane

12 June 2015 - 17 July 2015

The things we talked about: roomsheet

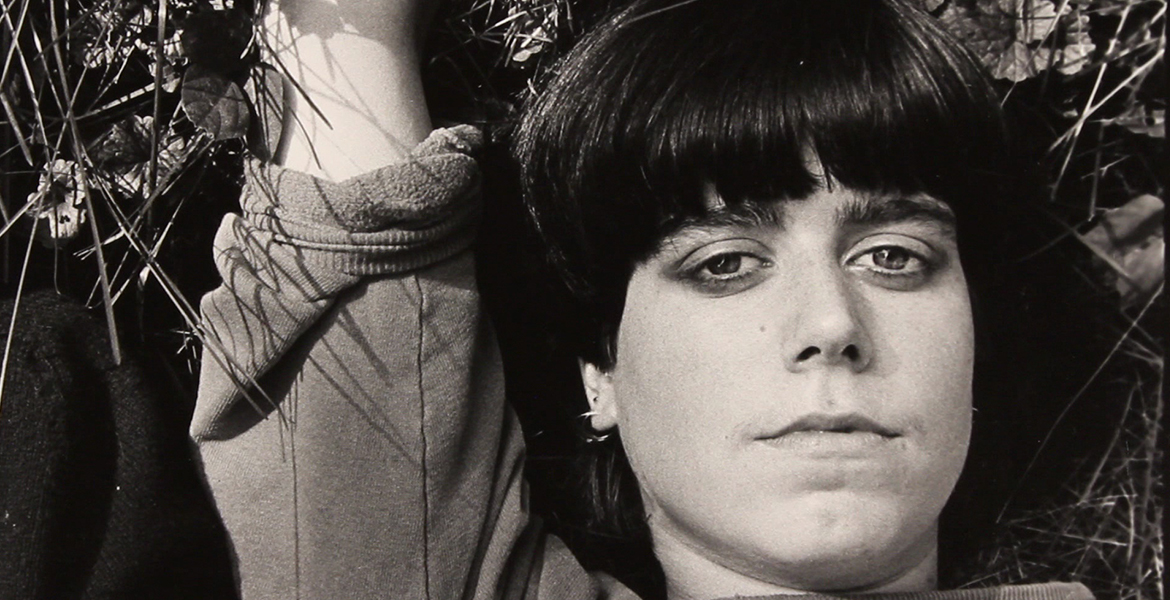

Moyra Davey, Les Goddesses (still), 2011. HD video, 61 Minutes. Courtesy of the artist and Murray Guy, New York.

Moyra Davey, Les Goddesses (still), 2011. HD video, 61 Minutes. Courtesy of the artist and Murray Guy, New York.

There are so many ways to remember a conversation. You might start with the tall-windowed apartment it took place in, the way voices sounded in the upholstered interior of a new car, across a swimming pool at night, or the way words sat on the page in a fax. This exhibition takes dialogue—listening, reading—as a primary currency. It sets out to consider how different visual forms afford spoken words weight, solidity, endurance, how they articulate relationships, and our sense of ourselves. Within the space of the exhibition a number of different speaking positions are adopted. Each might be understood as an autobiographical gesture, in the sense that your conversation is in some way definitive of who you are, as is what you read, how you listen, and how you spend time in a space.

Alicia Frankovich's Lover (2010) is a line drawing in neon. With the sparest of means the work implies the weight of a garment suspended from its coat-hanger, the impression left on a bed, the shape of a body, or the space where a body is not. Such absence is a condition of written correspondence; mostly, we write when someone is away and it has been too long. An individual letterform is at some level just a line—here that line is also a neon sign, a light, or a metaphor.

Ruth Buchanan's sequence of curtains divide up the gallery. Hessian, silk crepe, hand-dyed silk, they are easily moveable and semi-transparent yet compel you, as surely as solid architecture, to navigate the room according to their presence. The artist has spoken of them as editing devices, slowing or stilling the viewer's movements in a way that 'time-based' media does not. They introduce the idea of syntax, grammar, a spatial order which is readable by those who spend time in it.

Buchanan's work has consistently engaged the conditions of language, reading, research and cognition and their relationship to built spaces, suggesting that we don't just spend time in spaces, we think through them. Earlier works such as Build a Wall or Be a Room (2010) explore the psychology of architecture and our need for shelter, while her publication The Weather, a Building (2012), offers a biography of a building, the Berlin State Library. The curtains here have all had former lives in other installations; they have been reconfigured for this exhibition.

The Aachen Faxes (2012) by Marie Shannon records a correspondence (mostly by fax) between the artist and her partner Julian Dashper, during his residency in Germany in 1995. The faxes have been edited by Shannon so that they read as a continuous narrative, the breaks and gaps that characterise such exchanges removed, their rhythm that of a reader, and the paper converted to a monochrome screen. When it's not about the pragmatic things that must be recounted to someone familiar who is far away, the exchange is often about time. 'It's not that i'm having a bad time, as i'm not. It's just a slow time. This has to do with the way each day goes, and the sort of city Aachen is.' The slow time is also the time of the work, a pace become strange in contrast to the daily click/appear/click/appear of internet-time.

Shannon's editing is a kind of writing too; this time, from the distance of years, she revisits the everyday and specific references of the original text to construct a script for a different technology, and a different audience. Reading here is like remembering, the text a place to return to an earlier version of yourself you might otherwise lose sight of. The cello piece accompanying the text was written by Shannon and Mark Dashper.

Dorine van Meel's two video works in the show—Instead to meet strangers (2014) and At least the oranges come from Sicily (2015)—both use the voice as an instrument, providing a centre or beat. Instead to meet strangers recalls a letter she wrote as a teenager, to a future self. It was originally shown as a large scale installation at the Swiss Church in London, and features the prominent glass facade inside that church. In this work the site is flattened, it becomes an abstract diagram of the original, and we listen and watch partly for clues in order to make sense of the space.

At least the oranges come from Sicily also draws on multiple voices—written, visual, spoken. Two speakers read from a text that does not match with that on the screen, yet it is just possible to comprehend as a synchronous whole. The work is as much about listening as it is about looking, or the recognition that there's an inevitable correspondence between those two things. The artist writes, 'The autobiography is fiction because it can only be written once', and this idea underscores the fleeting anecdotes which populate the work. The spotlight effect which moves across the writing then retreats and erases it suggests language is limited by its own materiality; what is written now may no longer feel true tomorrow.

Private Hire (2015), a performance by lightreading (Sonya Lacey and Sarah Rose) where individual readings drawing on a legal case over intellectual property involving Rihanna and David LaChapelle were held inside a new Maserati, took place on opening night (see Artsdiary for documentation). In Private Hire the possibility of 'right and wrong reading', and the hyper-mediated state of contemporary communication comes into discussion. A pair of stylised sunglasses remain in the gallery after opening night, objects that speak the language of status, luxury, the manufacture of individuality and the decadent performance of privacy.

Window/Mirror (2015), a conversation between writer Sarah Jane Barnett and artist Ruth Buchanan, occupies the gallery's front window. The original exchange was by email—Sarah is based in Wellington, Ruth in Berlin—it comes to the space as a vinyl text on the window and a series of suspended posters that change each week during the exhibition. While the work Barnett and Buchanan produce separately is completely different, there's common ground in their interest in the materiality and mechanics of language, as can be seen in these unattributed texts. One reads, 'Where work really is a hinge in relation to something, a moving object that opens and closes, touches, squeaks, and breaks down too'; perhaps the dialogue's materialisation here is an instance of such break-down, a stopping by the side of the road to read, stretch or to look around. This conversation was conceived by Chloe Lane and Andrea Bell, editors of the journal Hue & Cry, who selected the fragments of conversation and handed them over to The International Office to design.

In Gallery Two, Les Goddesses (2011), a film by Moyra Davey, centres on the story of early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, her daughters and lovers. Wollstonecraft was an eighteenth-century British writer, philosopher, an advocate of women's rights, and the mother of Frankenstein author Mary Shelley. As the film progresses, narrative associations are drawn between their lives and those of the artist's sisters, recorded in still photographs from Davey's archive. Pacing her apartment with a handheld recorder, the artist narrates the story; occasionally subtitles interrupt, correcting the accuracy of her account.

Moyra Davey has very recently produced another film, Notes on Blue (2015), which moves through another tangle of biographies: this time those of film-maker Derek Jarman, poet Anne Sexton, writer Jorge Luis Borges, with the artist's own. Like Les Goddesses, the work might be described as confessional, but both are presented with a kind of atonal deadpan that makes that hard to reconcile. The space between fact and narrative contract in this telling; voice becomes both a 'place' where things fractured are brought together, and a 'time', the eternal present of the film's recording.

The significance of our ways of attending to things is the subject of social anthropologist Kathleen Stewart's book Ordinary Affects (Duke, 2007). She writes, 'People are always saying to me, "I could write a book." What they mean is they couldn't and they don't want to… The passing, gestural claim of "I could write a book" points to the inchoate but very real sense of the sensibilities, socialities, and ways of attending to things that give events their significance.' Speaking and listening are routine kinds of attentiveness. The 'things' spoken about in this exhibition are also mostly everyday; as simple as the arrival of the newspaper into an ordinary morning. It is the way these works pay attention to acts of speech, and to everyday things, that defines them; the ways they awake another sense of time, enable us to recognise particularities of speech, or shift the regular order of a space in a way that makes it read entirely differently.